Bad packaging design exposes common weaknesses in material choice, structural integrity, user experience, and information clarity. Recognising typical mistakes and learning from real-world examples provides insight into how products can fail in protection, usability, or compliance. Considering potential improvements, from material optimisation to clearer labelling and smarter design choices, helps guide packaging towards greater functionality, durability, and efficiency.

- What is a Bad Packaging Design?

- Which Common Mistakes Lead to Bad Packaging?

- 1. Over-Packaging

- 2. Inadequate Protection

- 3. Wrong Material Selection

- 4. Poor Dimensional Fit

- 5. Insufficient Closure Integrity

- 6. Confusing Labelling

- 7. Neglected Supply-Chain Constraints

- 8. Non-Recyclable Design

- 9. Excessive Complex Packaging

- 10. Untested Packaging

- What are Examples of Bad Packaging Design by Component?

- Excessive Plastic Use

- Hard-to-Open Packaging

- Misleading Labels

- Weak Seal or Closure

- Inadequate Cushioning

- What are the Consequences of Bad Packaging Design?

- Product Damage

- Logistics Inefficiencies

- Customer Dissatisfaction

- Brand Reputation Harm

- Regulatory Risks

- Environmental Burden

- Increased Costs

- Failure to Meet Functional Requirements

- What Makes Packaging Unsustainable?

- How to Make Improvements in a Bad Packaging Design?

- 1. Test with Real Users

- 2. Focus on Sustainability

- 3. Simplify and Streamline Design

- 4. Maintain Brand Consistency

- 5. Enhance Protection and Performance

- 6. Optimise for Logistics and Storage

- 7. Leverage Visual and Informational Clarity

- 8. Iterate with Prototyping and Testing

- What are the Major Differences in Good and Bad Packaging Design?

What is a Bad Packaging Design?

Bad packaging design is a packaging that fails to preserve product integrity, permit correct handling or meet regulatory and end‑of‑life requirements. Packaging consists of primary (product-contact), secondary (grouping), and tertiary (transport) levels, including examples like blister packs, retail boxes, and palletised cartons. Poor design shows structural failure, information failure, fit failure, closure failure, logistics inefficiency, and environmental harm.

Which Common Mistakes Lead to Bad Packaging?

Several frequent mistakes in design, material choice, and testing lead to packaging failures, each affecting protection, usability, cost, or sustainability. Some common mistakes in packaging are described below:

1. Over-Packaging

Overpackaging occurs when excessive materials increase the package size and weight. It typically happens during the design or specification of outer packaging and void fill. Examples include double boxes or oversized bubble wrap, which raise transport costs and generate unnecessary waste.

2. Inadequate Protection

Under-protection arises from inadequate cushioning or missing protective inserts, being most common for fragile or shock-sensitive products during transit. For instance, glassware shipped without corner protectors often breaks, leading to returns and damage claims.

3. Wrong Material Selection

Wrong material selection happens when materials are unsuitable for the product’s lifespan, environment, or recycling requirements. Supply chains are exposed to humidity, temperature changes, or recycling rules. Examples include water-sensitive paperboard in humid conditions or non-recyclable laminates for short-lived products.

4. Poor Dimensional Fit

Poor dimensional fit results from packaging or cushioning that does not match the product size. Poor fit occurs during the primary or secondary packaging stages. Loose packaging allows product movement, while overly tight packaging can cause compression damage.

5. Insufficient Closure Integrity

Insufficient closure integrity happens when adhesives, tapes, or seals are too weak to withstand handling. Failures occur during distribution, storage, or transport. For example, tape separation can lead to box opening, contamination, or spillage.

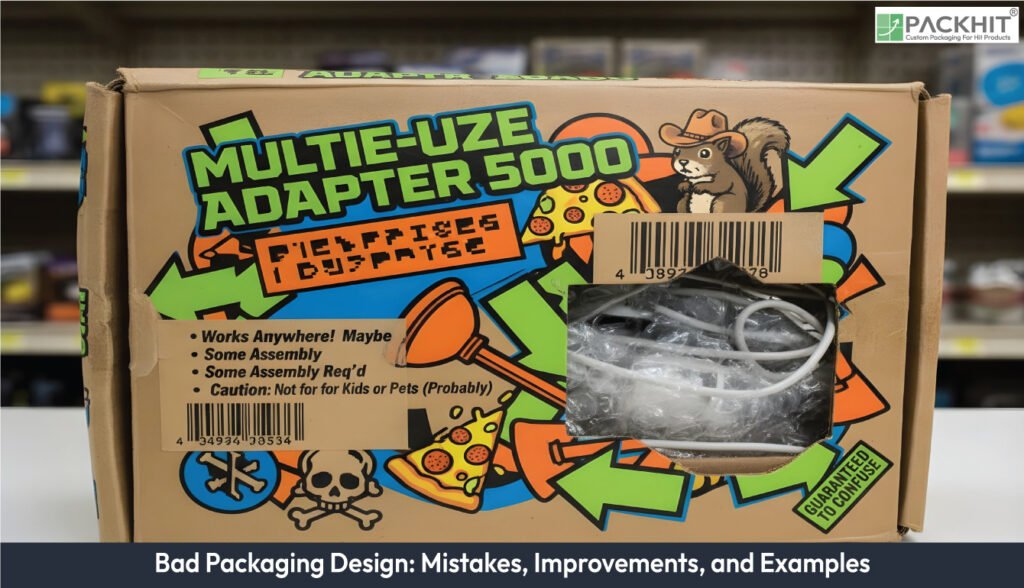

6. Confusing Labelling

Confusing labelling occurs when information is unclear, misplaced, or difficult to read, and happens on product packaging or user instructions. Misplaced hazard symbols or illegible ingredient lists can cause misuse and regulatory non-compliance.

7. Neglected Supply-Chain Constraints

Neglecting supply-chain constraints arises when packaging is designed for ideal display conditions but not for real-world handling. Damage occurs during last-mile delivery, cross-docking, or warehouse storage. For example, packages designed for shelves may collapse when pallet-stacked.

8. Non-Recyclable Design

Incompatibility with recycling streams happens when mixed materials prevent circular recovery. The issue arises during end-of-life processing or municipal recycling. An example is metallised plastic combined with paper, which cannot be separated for recycling.

9. Excessive Complex Packaging

Excessive complexity occurs when packaging is difficult to open or assemble, and affects the consumer’s first interaction during unboxing. Examples include glued inserts requiring tools or hard-to-open seals that reduce user satisfaction.

10. Untested Packaging

Failure to test happens when physical or environmental evaluations are skipped before production. Problems occur throughout distribution and storage. For instance, packages that fail drop or compression trials may reach customers damaged.

What are Examples of Bad Packaging Design by Component?

Packaging failures can occur at multiple levels, from outer cartons to interior cushioning, closures, labels, and food-specific barriers. Each component has distinct functional and protective requirements, and failure in any area can compromise product safety, usability, or regulatory compliance. The following examples of common failures illustrate the importance of matching materials, design, and testing to the product and distribution conditions.

Excessive Plastic Use

A consumer electronics brand packaged small items in large amounts of plastic, causing environmental criticism and loss of customer trust.

Hard-to-Open Packaging

A toy manufacturer used clamshell packs that required scissors or tools to open, frustrating parents and generating negative reviews.

Misleading Labels

A food company labelled a product as “organic” despite non-organic ingredients, leading to fines and reputational damage.

Weak Seal or Closure

A cosmetics brand shipped products in poorly glued boxes that opened during transit, causing spills and returns.

Inadequate Cushioning

A glassware retailer used single-sheet paper as padding, resulting in broken items and customer complaints.

What are the Consequences of Bad Packaging Design?

Poor packaging design creates mechanical, logistical, regulatory, and environmental problems that spread across production, storage, distribution, and consumer use. Below, each impact is expanded as a standalone failure mode to clarify how packaging faults appear in real conditions.

Product Damage

Product damage arises when packaging fails to absorb shock, resist compression, or maintain seal strength. Cracked glassware or leaking liquids reach customers if inner cushioning collapses or if closures lose adhesion during transit. Bad design, such as over‑glossed coatings or weak folds, often mirrors the defects seen in poor advertisement packaging, where structure and graphics lack functional balance.

Logistics Inefficiencies

Logistics inefficiencies occur when oversized cartons, excess void fill, or irregular shapes interrupt pallet patterns. Freight carriers charge more for dimensional weight, and warehouse teams spend extra time rotating or re‑stacking unstable units. Inefficient formats slow manual picking and reduce space utility across racks and vehicle decks.

Customer Dissatisfaction

Customer dissatisfaction develops when packaging arrives dented, difficult to open, or visually inconsistent with expectations. Tight clamshells, weak tabs, or warped trays frustrate end users and lower repeat purchases. According to a study, roughly 55% of consumers avoid items with inconvenient or damaged packaging.

Brand Reputation Harm

Brand reputation harm appears when damaged labels, faded inks, or inconsistent carton dimensions create doubts about product quality. Poor alignment, smudged graphics, or flimsy structures resemble the cues often criticised in bad design advertisements, and these signals reduce trust across retail shelves and e‑commerce listings.

Regulatory Risks

Regulatory risks occur when hazard symbols, ingredient lists, or recycling marks fall outside mandatory zones or fail minimum type-size rules. Incorrect claims, such as unverified “organic” wording, prompt fines or recalls. Packaging that obscures expiry dates or batch codes compromises traceability during audits.

Environmental Burden

Environmental burden stems from composites that cannot pass through recycling streams, such as paper laminated with metallised plastic. Mixed materials add contamination to sorting lines. Overuse of rigid plastics increases waste volumes and conflicts with retailer packaging reduction targets.

Increased Costs

Increased costs accumulate when excessive board grades, redundant inserts, or large print areas raise production expenses. Oversized packaging triggers higher transport fees. Poor pallet density increases energy use in heated or cooled storage zones and reduces container fill rates.

Failure to Meet Functional Requirements

Failure to meet functional requirements occurs when packaging does not contain, communicate, or protect according to product needs. Weak seams split if the humidity rises in storage. Labels lose legibility if coatings smear during handling. The breakdowns force repacking, slow dispatch operations, and degrade product performance.

What Makes Packaging Unsustainable?

Bad packaging design contributes to unsustainability through excess materials, multi-layer laminates, permanent coatings, or non-reusable structures. The bad choices increase environmental impact, complicate recycling, and raise transport costs. Design compromises occur when protection needs conflict with sustainability. Simplest solutions that maintain safety and shelf-life, such as mono-polyethene films instead of metallised laminates, balance product protection with eco-friendly design.

How to Make Improvements in a Bad Packaging Design?

Improving packaging design requires a holistic approach that integrates product protection, user experience, brand communication, sustainability, and operational efficiency. Effective strategies include:

1. Test with Real Users

Prototypes should be evaluated for usability, handling, and durability. Observing consumer interactions and feedback identifies potential issues before full-scale production.

2. Focus on Sustainability

Choose recyclable, biodegradable, or reusable materials to reduce environmental impact. Consider material reduction, mono-material constructions, and life-cycle impact when selecting substrates.

3. Simplify and Streamline Design

Remove unnecessary elements to create functional, clear packaging. Minimalist designs reduce costs, improve assembly efficiency, and enhance shelf readability.

4. Maintain Brand Consistency

Packaging should reflect brand values, aesthetics, and the target audience. Consistent colour schemes, typography, and finishes strengthen recognition and perceived quality.

5. Enhance Protection and Performance

Ensure the structure preserves product integrity during transport and handling. Incorporate cushioning, appropriate closures, and barrier materials where needed.

6. Optimise for Logistics and Storage

Design packaging for easy stacking, transport, and storage. Lightweight, right-sized packaging reduces shipping costs and warehouse space while improving sustainability.

7. Leverage Visual and Informational Clarity

Organise mandatory information, instructions, and barcodes clearly. Clear visual hierarchy prevents confusion and supports regulatory compliance.

8. Iterate with Prototyping and Testing

Use CAD models, physical samples, or AR simulations to refine fit, function, and appearance. Iterative testing ensures designs meet both consumer expectations and operational requirements.

What are the Major Differences in Good and Bad Packaging Design?

Good packaging design and bad packaging design choices impact protection, materials, information clarity, cost, and sustainability. The table below compares the characteristics of both:

| Aspect | Good Packaging Design | Bad Packaging Design |

|---|---|---|

| Protection | Preserves product geometry and function under expected distribution stresses | Allows product movement, overstress, or damage during handling and transport |

| Material Efficiency | Right-sized packaging uses recyclable materials compatible with recovery systems | Excessive material use, mixed or non-recyclable materials |

| Information Design | Places mandatory and consumer information in clear, unambiguous zones | Regulatory information buried, illegible typography, or poor hierarchy |

| Cost and Logistics | Minimises total landed cost through efficient material and transport choices | Increases costs due to over-packaging, oversizing, or inefficient logistics |

| End-of-Life | Aligns with recovery infrastructure and supports recycling or reuse | Fails to support recycling or reuse, causing environmental impact |

Understanding the major differences helps in taking better packaging decisions, ensuring products remain protected, information is clear, costs are controlled, and environmental impact is minimised.